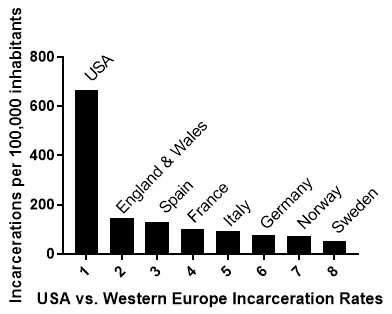

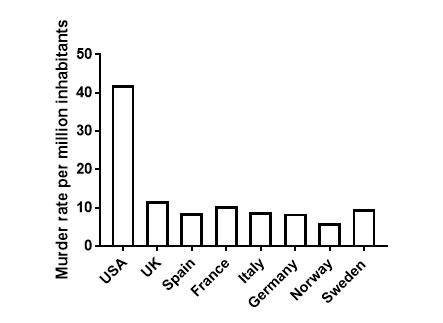

One of the most shameful aspects of prisons in the U.S. is that we incarcerate a far higher proportion of our population than any other country, six times more than the average in Europe, as illustrated in the chart below. We have 2.2 million in prison or jail in the U.S. It’s a problem I discuss in much more detail in my book The Costly U.S. Prison System.

Unfortunately, our higher incarceration doesn’t translate into lower crime statistics. For example, the U.S. murder rate is significantly higher than that of Western European countries, which have a considerably lower murder rate than that of the U.S., similar to the differences in incarceration rates.

Our prisons may be of higher quality than those in many Third World countries, but they do not compare well with those in many European countries. And we imprison far more people per capita than Russia or China, countries we consider to have terrible human rights records. What does that say about us?

In American Justice?, I characterized the U.S. prison system as a national shame. In addition, our incarceration rates have high economic costs that are much higher than they need to be to keep us safe. Instead, the money wasted on prisons could go to a much more worthy approach, such as making the much needed improvements of our infrastructure, improving our schools, lowering our national debt, or improving other aspects of our broken criminal justice system.

Following are a two examples of how the U.S. compares to other countries in putting convicted criminals in prison, and as case after case illustrates, the U.S. does not fare well. These other countries might serve as models in helping us bring much needed reform to our criminal justice system.

The Lessons of Prisons in Norway

While the U.S. represents one extreme of incarceration, Norway represents the opposite extreme. Guards there carry no weapons, prisoners wear no uniforms, and the courts are less punitive. The longest prison sentence, even for mass murderer Anders Breivik, is only 21 years, although it could be lengthened by increments later. Most Norwegian prisons are “open” and seem like country clubs to us.

They permit their inmates considerable freedom within the confines of the prison perimeter, allow them to cook their own meals, and provide them with considerable work training to prepare them for release. They even allow them to leave prison for work.

The prisons in Norway are small and located all around the country, and they allow prisoners to visit their families. Their prison cells look like dorm cells at a college. In some instances, they even have private bathrooms.

Norwegian prisons have these characteristics because the criminal justice system there emphasizes rehabilitation over punishment. One Republican congressman from Idaho noted the value of this approach when he asked, “What kind of person do we want leaving our prisons?” after he visited a Norwegian prison. Other officials from Idaho, North Dakota and Pennsylvania became convinced that our prisons can be made more humane, leading to better consequences upon prisoner release, since the recidivism rate in Norway and the rest of Scandinavia is far lower than ours. In response, these states have each been adopting some Norwegian prison principles.

Even Scandinavian high security prisons are less punitive than ours. As a result, it is easier for Scandinavian prisoners to take responsibility and blame themselves for their plight, rather than blaming other individuals, their disadvantages growing up, the prison environment, or society in general, as U.S. prisoners often do. Thus, Scandinavian prisoners are better able to express remorse and seek to change themselves to improve their lives upon release.

Norwegian prisons don’t have to deal with gang problems so prevalent in the U.S. and Norway spends three times more money per prisoner than we do, which would be politically unacceptable here. Nevertheless, Norway shows us that prisoners given sufficient positive reinforcement and skills have a much greater chance of succeeding upon release.

The Lesson of Prisons in Canada

Closer to home, examples in our hemisphere yield some similar lessons, most notably in Canada. One of the main lessons is that both incarceration rates and violent crime rates are much lower in Canada than for us, more nearly like Western Europe. A key reason is that Canada has a much more peaceable culture, while many countries in the Americas are wracked by drug wars and violence between gangs fighting each other for this trade.

Canada experiences less than half the violent crime as the U.S. and incarcerates fewer people. Part of the reason may be that there is basically no difference in violent crime rates between large urban centers in Canada and rural areas, in contradistinction to large urban centers in the U.S. Unlike the extent of urban crime associated with black poverty in the U.S., Canada’s black population is only about a quarter of that of the U.S., and no city over a half million has more than a 13.5% black population.

Homicide rates in Canada follow a very similar time course to those in the U.S., but Canadian rates remain approximately 3 times lower. Even when a crime wave hit, Canada did not increase incarceration. Violent crime and incarceration rates have both fallen since 1992. Violent crime rates similarly declined in Canada, as in the U.S. during this time, though at a lower rate, since Canada never experienced violent crime rates as high as the U.S. Under the circumstances, Canada never felt compelled to impose harsh sentences, with the result that mean and median sentences for violent crimes are very much shorter in Canada than in the U.S.

| Mean sentence in months | Median sentence in months | |

| Canadian courts | 10 | 2 |

| U.S. state courts | 71 | 36 |

| U.S. large county courts | 94 | 48 |

| U.S. federal district courts | 97 | 64 |

This difference could be very significant. Evidently, shorter sentences in Canada have not led to violent crime rates as high as those in the U.S.

There are a few other differences that might suggest ways to reduce the U.S. prison population. In 1999, about 9% of all Canadian cases went to trial, approximately double that in the U.S. Thus, less plea bargaining would help, although that would be expensive. In the 1990’s, Canada spent about $20 per citizen for legal aid (public defenders), more than double what we spend. More adequate representation for the indigent would certainly help reduce the number of inappropriate plea deals and reduce the casework overload of U.S. public defenders, and such defense representation would probably be less costly than more trials.

The clearance rate for violent crime in Canada is about 72%, much higher than the 46.8% reported in the U.S. More serious police detective work might help reduce crime statistics and take the guilty off the streets.

Restorative justice programs in Canada have been shown to reduce recidivism by almost one-half. These programs require convicts to apologize to their victims, work to provide restitution to their victims, and perform community service. This approach seems to work better with adults than with juveniles.

Summing Up

While I have used Norway and Canada here to show how prisons in other countries have lower incarceration rates and lower costs and are effective in reducing recidivism, there are many other countries around the world that can be used to show similar results, as described in The Costly U.S. Prison System. We can learn from other countries many ways to improve prison practices here.

In summary, prison policies in other countries suggest the following recommendations:

- We should increase the emphasis on rehabilitation as opposed to punishment.

- We should reduce sentence lengths and hire more public defenders and police detectives.

- The majority of prisoner wages should be used to make restitution to their victims.

- Prisoners should be instructed in a trade in order to make them much more employable upon release.

Paul Brakke is a scientist based in the Little Rock, Arkansas area. He became interested in studying the criminal justice system when his life was turned upside down after his wife was falsely accused of aggravated assault for trying to run some kids over with her car, since the kids and some neighbors wanted her out of the neighborhood.

Eventually, they were forced to move as part of a plea agreement, since otherwise, Brakke’s wife faced a possible 16 year jail sentence if the case went to trial and she lost.

He has previously told his wife’s story in American Justice?, along with a critique of the criminal justice system. That book’s website is at americanjusticethebook.com.

He founded American Leadership Books after he began investigating the criminal justice system in more depth. Thus far, five more of his books have been published by American Leadership Books.